The view from Mars Bay

|

Ascension Island Astronomy |

|

|

|

|

The view from Mars Bay |

My work occasionally requires me to travel to telemetry stations that track launches from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Our most remote tracking station is on the volcanic island of Ascension in the mid-Atlantic, west of central Africa. This six mile wide British possession has been inhabited continuously since Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled to 'nearby' St. Helena in 1815. Today Ascension contains many remarkably well-preserved relics of local historical note.

|

In 1877 David and Isabel Gill traveled to the island to measure the September opposition of Mars, which was being described as the best of the century. David, a noted British astronomer, wanted to use a heliometer and transit telescope to determine accurately the Sun-Earth distance, or astronomical unit. Such an expedition was a major undertaking in the 19th century, and Isabel later chronicled their experiences in Six Months in Ascension, an Unscientific Account of a Scientific Expedition. |

|

On a recent trip to Ascension, I sought out the Gill's expedition site. Isabel writes that they first observed from a naval garrison established 60 years earlier. Unfortunately, at that location clouds constantly obscured the night sky. With only a few days remaining before opposition, their measurements had to begin; the project seemed in jeopardy. One night, Isabel set out in search of clear skies, leaving her husband to fight the clouds for his measurements. Accompanied by a servant, she hiked across the lava plain. When she returned near dawn, she informed David that the skies were cloudless at a site several miles away. To salvage the trip they decided to relocate the heliometer and transit telescope. |

The move took three days. Royal Marine carpenters disassembled and reassembled their field observatory; this consisted of an octagonal, metal-pipe-and-canvas structure that housed the heliometer, and a more substantial wooden hut for the transit telescope. A crew of laborers was hired to carry the delicate instruments across miles of lava. A caravan of small boats delivered other supplies.

|

|

|

Mars Bay, where Gill's resupply boats put ashore.

|

|

To get there, I also had to hike across the island's lava plain. It is an unforgiving landscape, consisting of hills of hard gray and brown lava formations and scattered cinders. The wind blows constantly. With nothing to serve as landmarks navigation is tricky - I am amazed that Isabel made her way through it at night! |

As I crossed the lava field I found it surprising that anyone could survive there for several months as the Gills had - enduring the Sun, wind, and blowing cinders. The expedition depended upon barrels of fresh water and supplies delivered every Wednesday by a small boat from the garrison. Without the support of the British government and the Island Commander, Gill would never have completed his observations. Also consider that the Gills had to sail for weeks from England to arrive at what surely must have seemed like an alien landscape; too bad they had no way of knowing how similar the terrain was to that of the planet they had come to study.

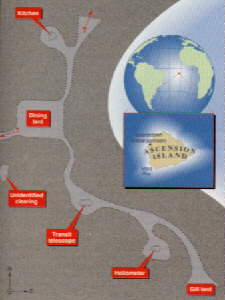

After about an hour of hiking, I located the the remains of the camp, confirming it with a sketch I had made based on descriptions from Isabel's book. The condition of the site is exceptionally preserved; the layout is still obvious 133 years later. Aside from the two telescope structures, there had been tents for dining, sleeping, cooking, and servants.

Because the nights and the dark color of the ground, the Gills had covered the paths between the tents and telescopes with white sand to make them visible by moonlight. Much sand still remains on the paths and around the clear, flat areas where the tents once stood. Isabel had lined the paths with small rocks, which remain virtually undisturbed. The telescope's brick and mortar pedestals endure also as a testament to the expedition. Now no more than weathered rubble, the piers rest upon flat rock formations slightly higher than the local terrain. The surrounding areas are cleared of debris and are also marked with sand. I was very surprised to find the site intact.

|

|

The image above is a stereo pair showing the location of the Gill sleeping tent. The small collection of shells she collected in 1877 are just to the right of center. Yes, they are still there. Cross your eyes until the images merge and you get the 3D effect. You may have to back away from the monitor a bit. |

One likely reason it survives is that it lies outside the usual hiking trails, so it hasn't been trampled by the curious or careless. In addition, there has been insufficient rain to wash away the sand put down during the expedition, and the lava plain does not support any grass that could grow over the remnants. The site has even survived nearby practice bombing runs conducted during the Falklands War.

|

|

| The view from 700' Gannett Hill, looking down at the lava plain. Mars Bay is top center, and their site about where the X is marked. A twenty foot thick layer of lava had oozed across the landscape (from left to right) in ancient times, stopping where it is at now. The resultant wall of rock is visible to the right in the previous Mars Bay photo. |

With the British government limiting access to Ascension Island, the site of the 1877 Mars opposition expedition is likely to remain pristine. Without so much as a small plaque to indicate its presence, the camp is all but invisible to passers-by; it is also probably unexciting to those who do happen upon it, but are unaware of its age and significance. Like the island itself, this landmark seems rugged and timeless.

To visit the observatory site now is to see it as the Gills did in 1877 - to experience the harsh remoteness they did, to hear the ocean and the sea birds, to see the night sky just as dark and impressive as a century ago. All that is missing is the flapping of the canvas tents in the wind.

|

| Above: One of a

very few vintage photographs of the Gill Camp at Mars Bay in 1877.

At right, Astronomer David Gills stands in front of the camp's big

tent. It is hard to see, but his wife Isabel is sitting down next to

him. The white sand path leads from them up to the Transit

Telescope,

and then on to the Heliometer (upper left). At left center are a pair of

African Kroomen workers. In the foreground, another assistant sits

on a shipping crate.

This photograph is from the Ascension Island Historical Society in Georgetown, Ascension. |

|

|

|

Another vintage photograph showing the Gills sitting in front of the main tent. The image is poor, but about the best showing both of them at the camp site. David Gill is wearing the light colored coveralls seen in the first vintage photograph. Note Victorian attire of Isabel. This photograph is from the Ascension Island Historical Society in Georgetown, Ascension. |

|

|

| The location of the kitchen tent is still recognizable, perhaps the best preserved part of the site. The path leading off to the lower right becomes the white path entering the vintage photo from lower right. |

I returned to the Gill Site in June 2001 and 2008, and found it much the same as I had in 1994. The paths are still very recognizable. Shells collected by Isabel are still there.

all color photographs copyright 2015 Thomas G. Cave